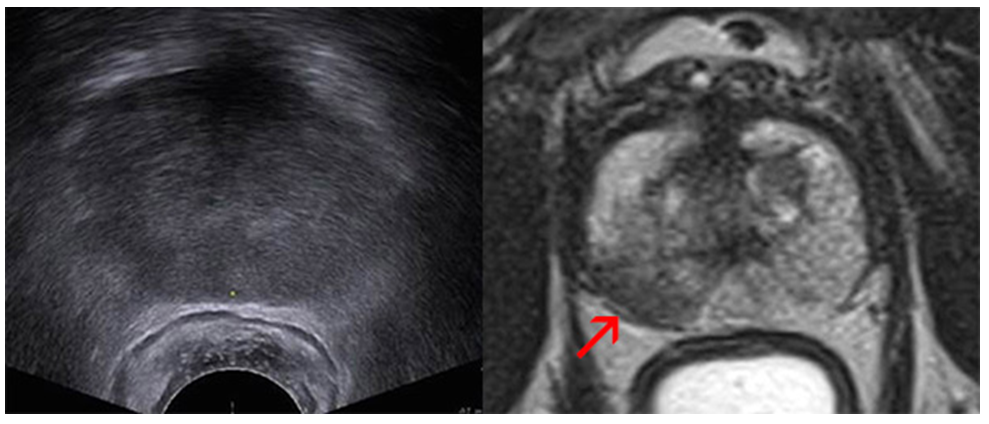

What are the benefits of the MRI fusion biopsy?

- This technique allows our specialists to find hidden tumors that may be missed by other prostate biopsies.

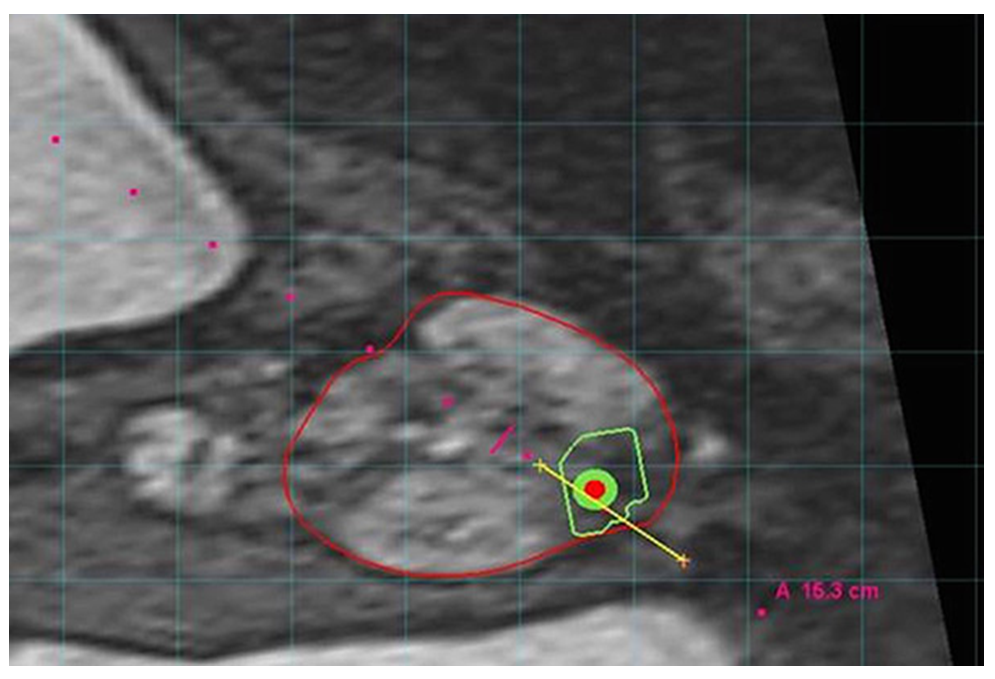

- We can perform targeted biopsies using sophisticated MRI/ultrasound fused images to focus on the worrisome areas directly.

- The technology, which has proven to be very useful for men with previous negative biopsies, may also help detect aggressive cancers in patients who have not had a previous biopsy.

- It may reduce the number of biopsies you need

You may be a candidate for this procedure if you have:

- An elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) score

- An abnormal finding on your digital rectal exam (DRE)

- A history of negative traditional biopsies with a continued concern for cancer

The MRI Fusion Biopsy is not perfect.

Please remember, the fusion guided biopsy approach isn’t perfect. A recent study found that the fusion method may miss many prostate tumors just like the standard biopsy. But the cancers that the fusion method misses are far more likely to be clinically insignificant. Put another way, fusion guided biopsy is better than the existing approach at finding prostate tumors we need to treat, while overlooking those we don’t need to worry about.

Preparation for the biopsy

You cannot take aspirin or other blood thinners, such as Plavix, Eliquis, Brilinta, Pradaxa, Coumadin, Warfarin, Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Aleve, Advil, Celebrex, Ecotrin, and many others for several days prior to your scheduled biopsy. If you take any of these or other anticoagulants please discuss this with our scheduler. It might be necessary that you also consult with your Cardiologist prior to stopping.

The day before the biopsy

The night before your exam, you need to take an antibiotic as prescribed by your physician before going to bed. If you have not received any prescription for an antibiotic please contact our office immediately.

The day of the biopsy

The morning of the exam, give yourself a Fleet enema two hours before your biopsy, which is available over the counter and follow the instructions on the packaging. The enema helps to clean out the rectum and to minimize the risk of infection.

You should take your usual medications, except for the above-mentioned blood thinners if applicable.

If you have undergone a recent artificial joint replacement (<6 months ago) you might need to take additional antibiotics about 1-2 hours prior to the biopsy. Please notify the office if you have a recent history of such procedure, or if you usually take antibiotics before e.g. dental procedures.

After your biopsy

Please be sure to finish your antibiotics as prescribed. If you did not receive office anesthesia, there are no restrictions on driving after the procedure. If you received office anesthesia, you must have a driver available.

Biopsy results are typically available in 5-7 days. Your ordering healthcare provider will be notified of the results, who will then share them with you at your follow up appointment or by phone.

Possible side effects from the biopsy

Hematuria (blood in the urine) is the most common complication after prostate biopsy (20 to 63%), is usually only very slight, and subsides usually completely after a couple of days.

Hematochezia (blood per rectum) is common as well, and seen in 2% to 22% of patients. Typically, rectal bleeding is minor and easily controllable with the ultrasound probe or digitally applied pressure at the conclusion of the biopsy; rarely, persistent bleeding may require proctoscopic assessment.

Hematospermia (blood in the ejaculate) is of minor clinical concern and is found in up to 50% of men after their biopsy. It may persist for several months after prostate biopsy.

Most infectious complications after biopsy are limited to simple urinary tract infections and low-grade fever, which can be readily treated with antibiotics. With the routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis as described above 2% of patients will develop a febrile urinary tract infection, bacteremia, epididymitis or acute prostatitis that may require hospitalization for i.v. antibiotics.

Acute urinary retention requiring temporary intraurethral catheter placement occurs in up to 0.4%; mostly men with an enlarged prostate (BPH) at baseline are at increased risk.